My neighbor Ben’s been dead since spring,

his memory gone for longer, yet

his driver’s license sits in my car —

stuck, I think, to the base of my backpack

when I set it down on a postal counter

where someone — widow or executor — must’ve

left it behind, their own mind rocked

by too much grief-smog smothering the have-tos.

Once I thought I heard my mother calling

clear across a KMart, even though

I knew I’d left her dozing or dazed

on a couch at home — some semblance of resting

while I dealt with errands that could not wait

— and, truth be told, also some chores

that let me stay away from the house

a little while longer, to breathe off-script

away from the memories — never to line up,

hers against mine — of what should have been.

Or, let’s be precise, of what we wanted to insist

the memories should have been. I hear Ben sang

a lot of hymns in his time. My fault,

among my many others, not making time to hear

the singing, though I feel not guilt,

just sadness. Clutching and squeezing a watch

won’t make its face roll out any flatter

or wider. Time is not a piecrust one

can stretch or lattice into enoughness,

no matter how many badges one collects

for working instead of sleeping, for other

bargains with devils and demons. I shall

make time, this next new year,

to hold what sweetness it can, but also

let it crumble and flake, as it must,

like pastry and soil and other layers

from which good thoughts may somehow emerge.

Introduction by Sherry Chandler

Hello.

Or in the immortal words of Cousin Minnie Pearl — How DEE, I’m just so proud to be here.

Mary Alexandra Agner invited me to add my voice to the harmonies here, a timely invitation for me, serendipitous even, though I use that word with caution.

I wrote a blog for several years but one day I discovered I couldn’t do it any more. I think they call that burn out. Lately, however, I’ve felt an awakening of the urge to blog, accompanied by a reluctance to take on so intense a task.

So when Mary’s invitation showed up in my inbox, I accepted joyfully. It seems as just right as Baby Bear’s chair. I like what I read here and hope I can contribute something worthwhile.

Is this a preamble or just an amble? I really don’t like introducing myself. My life story is available at sherrychandler.com. To give you a notion who I am, I’ll give you a poem from my book Weaving a New Eden. The poem culminates a geneology in poems following mothers instead of fathers.

Sherry Florence Chandler

(daughter of all of these)So I am arrived here, not in the plumb-bob

Heritage of my father’s line, my father called

Eagle-eye because he could raise a barn foursquare.

Rather I am come in zigs and zags, a looping

Ragged line of mothers and grandmothers, nested

Yarn, a thread spun, woven, hooked into coverings.Fancy finds these women plain, and poor, working

Land farmed out since the first generation plowed

On clear-cut hills. Time’s mainstream washed past like

Rivers and creeks that took their topsoil, left only

Eden Shale, academic term for sticky yellow clay.

Nurture in such an Eden was a fulfillment of God’s

Curse, toil and pain, and yet, from this unwelcoming

Earth they brought forth lilacs and tender lettuces.Cuttings and seed, handed on, handed down,

Homespun petticoats, spinning wheel on the hearth,

A loom in the barn, then feed-sack frocks, the reciprocating

Needle of the Sears and Roebuck Singer in the corner.

Daughter of all these, I would sing for these women

Like Virgil – strong arms and the woman –

Except, of course, that that is not their style.

Rather I’ll call you a dance to the figure of the Black-Eyed Girl.

Aubade (first draft)

I wear the sun on my arm to say

Nothing can be true or total all the time:

Ink blurs and bleeds, features fade,

and I have been called a thousand names

that weren’t my own, sometimes with malice

and often within a miasmatic memory’s

failure to ever-fix my mark among its grooves.

I shall not be greedy. Two hundred years hence

we all shall be writ in water and fire —

dead light lacing the streaks of diamonds

plummeting into planets no plutocrats can plunder.

What is a treasure no tyrant can touch

or tax — what shall we call currency

that cannot be spent or shared? Under my pillow,

I press my palm to a coin from Taiwan,

tracing not the actual engravings —

a dictator’s face, a palace-museum

I played within but have no precious

recollections to cherish, precise

or otherwise — I finger the metal,

trying to melt into sleep, the better

to stay alive and sane, the better

to be not constant nor correct for all time

but often enough — just often enough,

just enough, often just, often adjusting —

you see how it is? Let me not

to the marriage of minds

deny the truth of impediments:

I am no compass, but I am the moss

that glows jewel-green on even mundane days

and coats the trees on trails,

a mute map through midnights.

Swimming Together (Review)

The aim of this anthology is to promote the connection between humans and marine animals, and to highlight the variety of marine animals. The anthology’s introduction states, “[We] were motivated by the urge to celebrate the exhilarating variety of ocean wildlife….while also bearing witness to the shattering reality of their plunging numbers.”

I found the poems in the anthology to spend a lot of time on the latter: explaining to me this animal or that but saying little more than “here’s an animal.” Notable works which break that mold include

- Meg Files’ “Penguin Parade”, for going somewhere unexpected

- Christina Lloyd’s “Car Wash”, for starting somewhere unexpected

- Beth McDonough’s “Flatly”

- Kathy Miles’ “Hydromedusa”, for its turn

Given my interest in poetry which uses devices such as assonance, consonance, repetition, and rhyme, I paid close attention to the form of the anthology’s poems. In the majority, they are free verse which does not utilize these sonic devices. The main exception is Andy Brown’s wonderfully musical “Oyster Shells”. Kathleen Jones moves her “Whale Fall” in the directional of musicality through her use of assonance. And Sharon Larkin’s “View from the Benthos” makes its own music through scientific jargon; a real treat.

Two other poems stood out to me. Donna J. Gelagotis Lee’s “Fishing for an Octopus” is one of the few poems that actually comments on human-animal interactions and does it superbly and with a dark twist. Bryce Emley’s “To the Bumblebee Who Landed On My Stomach At High Tide” got my attention for the amazing sentiment in its first line and for stretching the definition of “marine animal” in a way no other included poem did.

While I find myself very much agreeing with the editor’s motivation, less than a quarter of the poems exhibited, to me, the exhilarating variety of musical device.

introducing Dawn McDuffie: “Where do you find these ideas?”

Dawn McDuffie is a wonderful woman whom I’ve had the good fortune to know since the mid-1990s; we met at a YMCA Writer’s Voice workshop in Detroit. For the past twenty years (!) or so, we’ve corresponded about applications, books, church life, dolls, eats, and a good many things beyond. This is her first post for Vary the Line; please check back each month for more insights from Dawn (and the rest of us).

Where do you find these ideas?

I spent an hour or so this afternoon watching a pair of monarch butterflies flit from yard to yard. The four households own tiny city lots, but the homeowners have stuffed them with flowers and tasty milkweed. It seems unfair that the grace of butterflies, the changing of colors as one perennial blooms and another dies back — that all these riches didn’t inspire a new poem, although I did write a haibun last year during a terrible drought. In the same way, the current political state has sparked a sense of dread, but has not given me any poems. I’m grateful that somewhere between pure beauty and total distress I find possibilities lining up, waiting to be written. Here’s the haibun from last summer’s heat wave:

Detroit, summer 2016

7:00 A.M. and it’s 80° in our back yard, a small space surrounded by a high fence, and most years, the green of shade and sun, regular rain. Tangerine day lilies, pink lilies, coral bells with their sparkle wands tolerate the dry part of summer, but none of our plants can stay healthy with no rain at all. Summer thunder storms have passed us by. I go to bed with a glass of water on the night stand, just in case I’m too thirsty to sleep. In the morning I pour what I didn’t finish into a black plastic watering can. Seedlings, I’m sharing my drink with you.

Thirsty hummingbirds,

I have watered the bee balm,

cool gifts quickly gone.

Introduction by Lisa Dordal

Hello! My name is Lisa Dordal. I am a Nashville-based poet and teacher and I was recently invited by Peg Duthie to join this group as a monthly blogger. It took me a long time to realize I was a poet so I thought I would spend this first post talking a little about my journey as a poet.

I grew up in Hyde Park, a neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, as the youngest of four. Our house was full of books and there was a strong emphasis on academics–particularly on math and science. The message I received growing up was that logic and empiricism were superior to feelings and personal experience. I did not excel at either math or science, so I spent a good portion of my childhood and early adulthood feeling inadequate academically–as well as denying the importance of my feelings. I wrote some poetry in high school and college but then nothing for many years. It simply didn’t occur to me that poetry was something I should be taking seriously. Having been told my whole life that there was only one legitimate way to acquire knowledge–one dominant and correct orientation for wisdom–I spent years feeling out of sync in terms of my ability to learn about and experience the world.

After I graduated from college in 1986, I worked at a variety of support-level jobs. Then in 2001–at the age of 37–I decided to go to divinity school. I had been a Religious Studies major in college and had also briefly pursued a master’s degree in feminist theology in my late 20’s. I never felt called to enter the ministry; I only felt called to go to divinity school. During divinity school, I was drawn to studying the Bible. I wanted to learn as much as possible about this text–or texts–in which women appeared to play such a minor role. I wanted to somehow crack open the stories so that I could hear a fuller story. During my last year of divinity school, I began to write poems in which I creatively re-imagined certain key stories in which women appear only peripherally. My point was to give these women a kind of voice–or at least my version of a voice–that had long been denied to them.

The same year that I graduated from divinity school (2005), my partner, Laurie, spotted an announcement on the Vanderbilt webpage for a weekly poetry workshop that was going to be starting that fall and that would be open to anyone from the Nashville community. She forwarded the announcement to me with a message saying I might want to consider signing up. It turns out that signing up for this workshop was the beginning of a whole new journey. Several years later–and many poetry workshops later–I applied and was accepted to Vanderbilt’s M.F.A. program in Creative Writing. And there I was–at the age of 45–a full-time graduate student.

Prior to enrolling in that first poetry workshop back in 2005, the only poetry I had been exposed to was whatever poetry had been assigned to me in my high school English classes or in the one literature class I had taken in college. Poetry, quite frankly, scared me. On the one hand, I was scared by how little of it I understood and, on the other hand, I was scared by how removed it seemed to be from the more “serious” pursuits of, say, science and math. Through my classes at Vanderbilt, I was introduced to a wide range of poets, and it was in the process of finally reading lots of poetry that I began to feel a sense of homeness inside of me–a sense of deep contentment as, finally, I was able to feed the deep hunger I had for knowing the world in the way that I needed to know the world.

This is what had been missing from my life for so long: the kind of radical, visceral, feeling-based immersion into the world that, for me, would come from reading and writing poetry. By immersing myself into poetry–by lowering myself into it–I am, at the same time, being lowered into the world, past and present, in a wonderfully embodied way. When I read poetry, I feel physically affected by it. Something happens inside of me.

Sometimes when I read a poem, it feels as if I am entering a room, a room in which every word has been loved into being; other times it feels as if I am walking along a wooded trail–as if each line of text is a path I must follow, must gladly follow. When I experience poetry as a kind of walking, I am aware of how much reading it slows me down. Poetry is sometimes described as language in which every word matters–take away one word and you take away the poem. When I enter the world of a poem, I am entering a world in which every word must be paid attention to. Slow, meditative attention. This slowing-down effect is particularly helpful to me at those times when I am feeling depressed or just generally overwhelmed by the events of the world around me. Reading the work of some of my favorite poets, slowly and meditatively one word a time draws me back to my center, to the present-ness of the moment. The French philosopher Simone Weil once said that absolute attention is prayer. The act of reading poetry is a way of paying absolute attention and, thus, for me, a kind of prayer.

Too, when I read poetry, I know that I am not alone. I know that my life is bound up with the lives of others in this strange and wonderful and too often profoundly painful narrative of life. And when I write poetry, I know that I am not alone–that, in the process of writing, I am being led towards something bigger and deeper than my life alone. And it is in this feeling of transcendence–this feeling of connection to the larger web of creation and the web of human history in particular–that I feel a sense of deep, deep joy.

So, that’s the slightly condensed version of my journey. And now I’d like to share one of my poems that was recently published in Ninth Letter. I won’t always be sharing my own work on this blog–there’s plenty of poems from other poets I’d like to share here–but I figured this poem sort of relates to my journey of becoming a poet. Here’s the link:

http://ninthletter.com/web-edition/summer-2017/summer-2017-poetry/217-dordal

Until next month,

Lisa D.

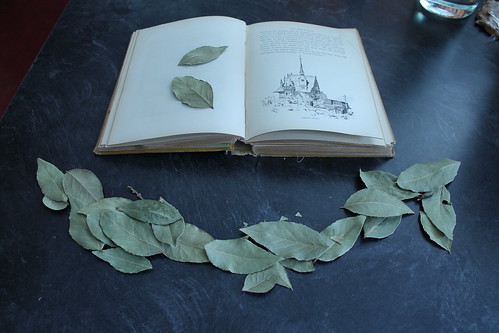

At Bay

The leaves my sister

told me to throw out

reminded me of books

I hadn’t read in years

but then I saw

that only the veins

matched the antique pages.

So much for spinning

some spiel about stories,

spices and sauces —

how almost everything fades,

dries out, flickers

into dirt and dustbins. Yet

to greet this morning

with such abundance —

how immense, how marvelous

to sit for a while

with obsolete leaves

and then to cast them

upon last year’s wreaths

decomposing

amid the scraps

of ordinary meals. What

a luxury, this space

to not need what’s at hand

and time to study it anyway —

a few final minutes

of not yet moving on.

Singing Colors (Review)

Scriptorium: Poems, Melissa Range, Beacon Press 2016

Melissa Range’s Scriptorium concentrates sounds and sights to weave together poems on the topics of Appalachia, Christianity, and the natural sources turned into ink for use by Christian monks in Europe during the Middle Ages. While perhaps disperate-sounding topics, Range uses the colors of the titular scriptorium as a backbone to structure the topics for the reader.

Verdigris, orpiment, kermes red, ultramarine, shell white‐these are a few of the colors Range writes about in a series of sonnets, enlightening the reader to the creation process and source animal, mineral, or vegetable of the inks. Opening “Woad”, Range writes

Once thought lapis on the carpet page, mined

from an Afghan cave, this new-bruise clot

in the monk’s ink pot grew from Boudicca’s plot—

a naturalied weed from a box of black seeds found

with a blue dress in a burial mound.

But whatever the range, ahem, of topics, Range’s musicality on the page is what stays with me. Take, for example, “Pigs (See Swine)” which is 32 lines, eight quatrains, of monorhyme, one rhyme sound for the entirety of the poem. The second stanza goes

But there’s a book whose pigskin bindings shine

for youth and aged alike, in which the terms align,

pigs and swine; and in its stories, sow supine,

your litter’s better bacon in a poke done up with twine.

Other flights of music I loved include “Anagram: See a Gray Pine”, “Hit”—really, most of the poems about how they speak where and when Range grew up. Range wrings music from the most simple and the most complex of English words but even at the syllables’ most simple, her meanings are multiple and deep and worth reading.

Bouts-Rimes for Hope

Either poetry is dead or it is what people turn to in times of need, at least according to the Internet.

I asked a number of my poet-colleagues to write for hope, to help people during difficult times.

The result is a small chapbook of sonnets you can download for free: EPUB or MOBI (Kindle) files here on Gumroad. (Just enter 0 for the price.)

The chapbook contains poems by Carol Berkower, Sherry Chandler, Peg Duthie, Jenny Factor, Annie Finch, Cindy M. Hutchings, Marc Moskowitz, Charles Rammelkamp, and Mary Alexandra Agner.

If you, in turn, should pick up pen to reweave these end-words, originally borrowed from Edna St. Vincent-Millay, to write your own piece of hope, please share it with us here by leaving a comment with a poem or a link back to your own post with a poem.

Spirit Speech (Review)

A Field Guide to the Spirits, Jean LeBlanc, Aqueduct Press 2015

The poems in Jean LeBlanc’s A Field Guide to the Spirits cover a range of subjects, opening with mediums and ghosts, dipping into nature and natural sites, famous natural scientists of the 19th century and their family members, and historical figures from even older periods, before returning to the titular poem of the collection.

LeBlanc’s work is not rife with musical device; you will not find sonnet or alliteration here. I found the lack of musical device, usually intended to make a phrase memorable, a bit ironic given that the topics of so many of the poems were things to be remembered or involved remembrances by their speakers.

What LeBlanc’s work gives you is the surprising point of view—be it person or place—and the stunning epiphany.

For example, her “Hope, Hunger, Birds” does indeed trace a trajectory between those three concepts, although not in that order, and begins and ends in such different but related places that you cannot help but feel moved. I loved that the epigraph was by Susan Fenimore Cooper. It’s difficult to pick out just a few lines because it is the context they build together that is striking, but I keep coming back to these:

Like a songbird, my old heart,

still believing it will see another spring, craving

every tender blossom, wanting more.

In these poems, I appreciated the presence of Caroline Herschel, Catherine Barton (Newton’s niece), the unnamed woman describing how the town elders inspected the underwear of a group of women, especially her last snarky, surprising line. There is a lot to learn here; LeBlanc presents vivid portraits that made me, as reader, want to know more in the cases where I did not.

While she may not employ the poet’s arsenal of musical device, LeBlanc certainly understands it. In “Eleven Reasons Not To Marry A Poet,” she writes,

They are enamored of pretty words, but most especially of the saying of pretty words. You must be careful not to believe beyond the final iamb.

Indeed, it is the space beyond that final iamb which LeBlanc’s work explores.